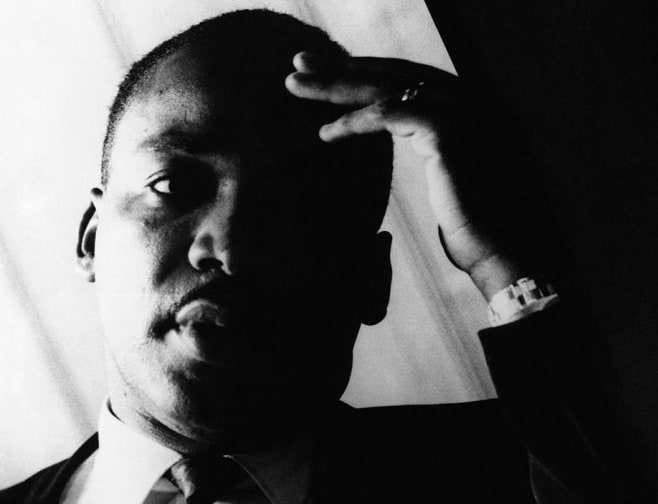

The massive strides of the civil rights movement under Martin Luther King Jr.’s leadership — the bus boycotts, sit-ins and marches — have been widely covered in both narrative and nonfiction films, as has the 1968 assassination of the revered desegregation activist. But less attention has been paid to the troubled interim period, during which King faced criticism from the Black Power movement, who found his resolutely nonviolent stance ineffectual, as well as the anger of President Lyndon B. Johnson over his vocal opposition to the Vietnam War. Documentary filmmaker Peter Kunhardt undertakes a thoughtful examination of those final years in his engrossing tribute to a complex legacy, King in the Wilderness.

Premiering at Sundance ahead of its HBO bow, the documentary taps into a regrettably still relevant debate as America backslides in the wake of last year’s Charlottesville protest, with white supremacist fringe groups newly emboldened in the Trump era. As such, the film’s message remains timely, shaped by the voices and vivid recollections of King’s intimate associates in the struggle for equality. As one interviewee puts it, quoting an African proverb: “If the surviving lions don’t tell their stories, the hunters will get all the credit.”

Superb archival footage is interwoven with the talking heads. None of it is more chilling than the image of a preteen white boy playing “Dixie” on his clarinet on the sidelines of a 1965 march in Mississippi, flanked by his Confederate flag-waving sister and pausing only to shout “Go home” invective at the peaceful African-American protestors.

Kunhardt and writer Chris Chuang focus on the increasing fragmentation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in the wake of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That breakthrough legislation was followed directly by the Watts riots in Los Angeles, prompting King to expand the civil rights organization’s influence to segregated Northern cities at a time when many felt the work in the divided South was far from complete.

King shifted the mission beyond undisguised racism to target complicated issues of poverty, housing, unemployment, education and police brutality. He moved the central SCLC think tank to the Chicago slums, causing friction with long-serving mayor Richard J. Daley, as a different kind of hatred and segregation were exposed in Illinois. But resistance to giving African-American Southerners the vote inflamed racial unrest in states like Mississippi and Alabama. After the shooting of James Meredith, who led the March Against Fear, King returned to the South, his immutable core principle of nonviolence proving at odds with the growing Black Power movement spearheaded by Stokely Carmichael.

That schism in the summer of 1966 was the first real breach in the nonviolence movement; associates stress that while King understood the anger and frustration of Carmichael and his supporters, he remained convinced that patience and reasoning were the way to go. However, when he was pulled against advice into taking a stand on the Vietnam War, he rankled the White House, intensifying the hostile scrutiny and sleaze tactics of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Editorials condemning King for crossing the line into government matters caused a backlash, but despite his growing isolation and fatigue after 12 years of nonstop struggle, he continued to put his weight behind the Poor People’s Campaign, which culminated in the 1968 March on Washington.

The filmmakers assemble a dense portrait of a man disheartened by his failure to move the needle on economic justice, even as he succeeded in tracing ties among the common problems facing blacks, Latinos, Native Americans and even low-income whites. This midsection gets slightly bogged down in detail and could benefit from tightening, but the buildup to King’s assassination is expertly handled, as is the shattered aftermath.

Moving personal observations come from, among others, Jesse Jackson, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez and SCLC officials including Andrew Young, C.T. Vivian and Bernard Lafayette. Perhaps the most affecting memory is that of civil rights leader Xernona Clayton, who recalls taking out her powder compact to disguise the clumsy work of the mortician on King’s face, when his body lay in state at Spelman College. Wrenching footage of his father, the Rev. Martin Luther King Sr., collapsing distraught by the side of the coffin deepens the emotional wallop.

Complemented by composer Saul Simon MacWilliams‘ subtle scoring, Kunhardt’s film eloquently reiterates the case that King’s assassination is one of the historical tragedies that define America, and that his push for social change speaks with as much clarity and urgency today as it did a half-century ago.